Capítulo 1: Panamá Panamá Panamá

Podré ser un sentimental, pero a mí me encanta cuando me encuentro con un pedacito de mi Patria en una película. Seguro ni tengo que recordarles que Godzilla pisó Panamá en 1998:

Pero, ¿sabía usted que Saul Goodman mantenía un pasaporte panameño en su caja secreta de documentos?

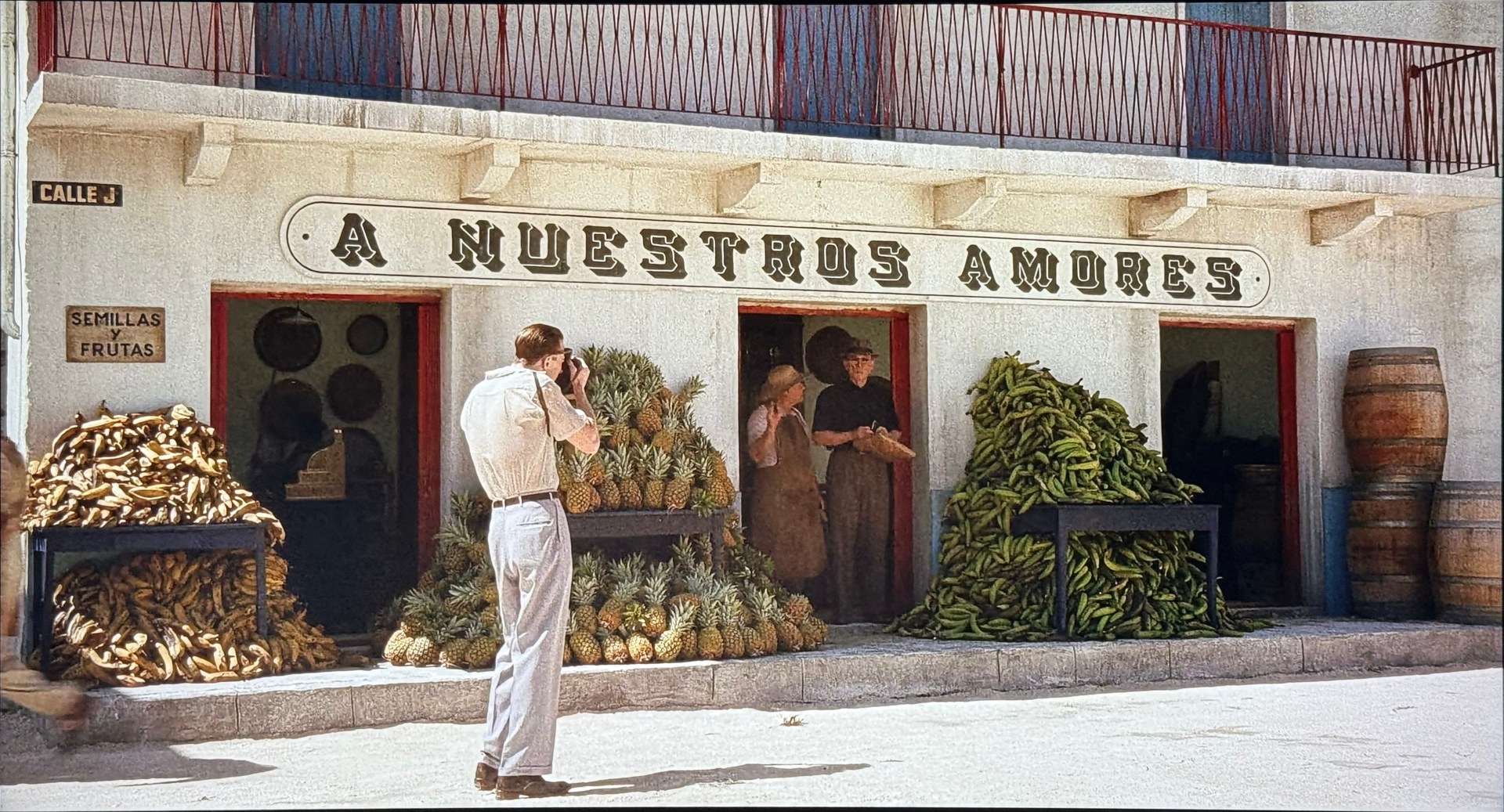

Hoy estamos aquí para contarles la última vez que eso hashtag me pasó. Si estuvieron entre los doce o trece que alcanzaron a ver Queer de Luca Guadagnino antes que la quitaran de cartelera, o si están bendecidos con una cuenta de MUBI, seguro saben de lo que estoy hablando. Mírenme esta belleza: el viaje a Suramérica de Lee y Allerton arranca con un montage panameño. Primera parada: una frutería en Calle J para preguntar por “H and C (heroine and cocaine)”. La respuesta del vendedor, tras una carcajada en español: “You can get those in the city, en el canal”.

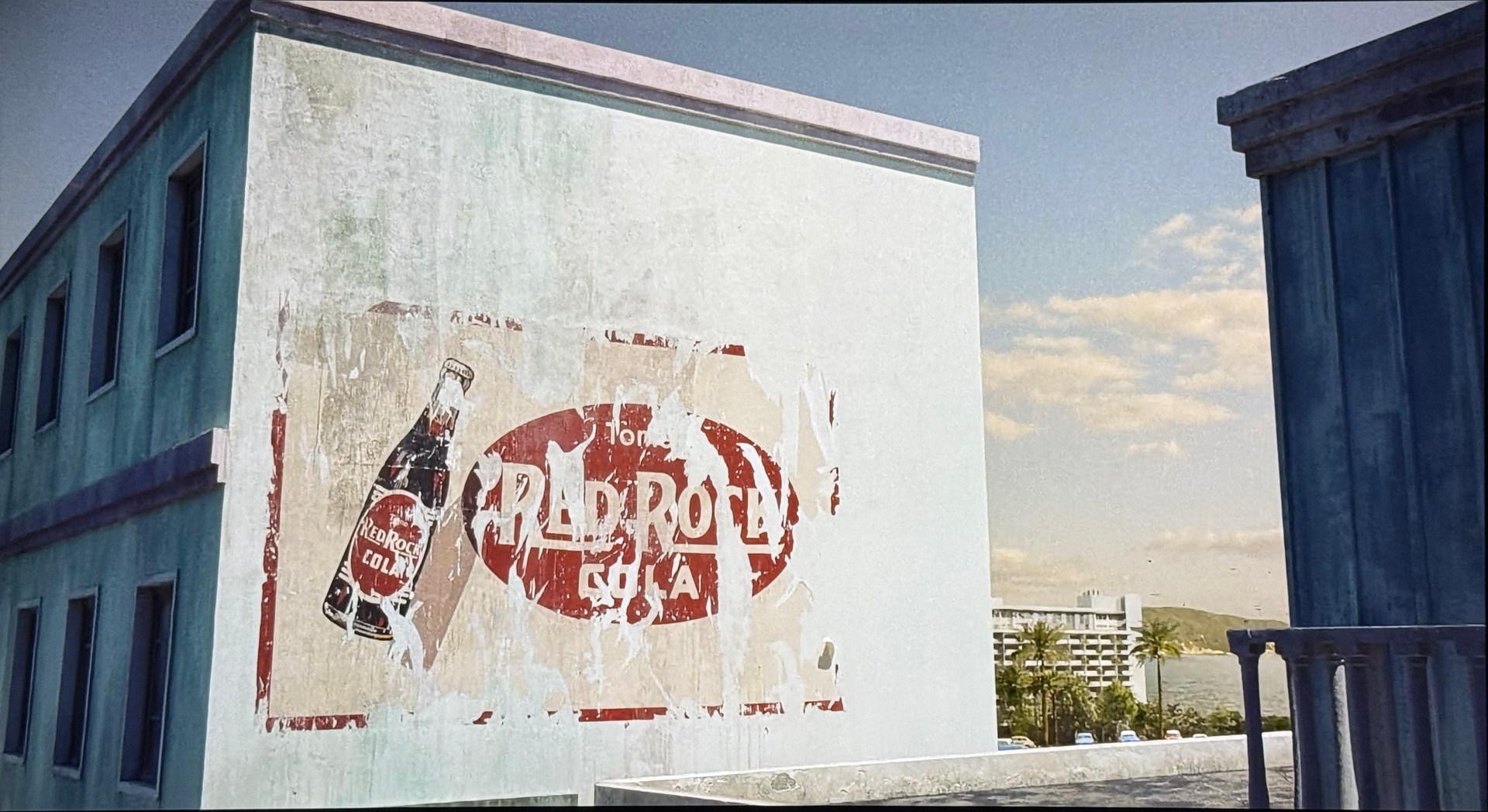

Después, mientras Prince canta Musicology, nuestros viajeros pasan frente a una cantina y un billetero:

Que resulta estar al lado de las esclusas del canal, con el cerro Ancón al fondo, y (redoble de tambores por favor) una fonda que se llama El Ganso Azul. Acuérdense de esa.

Después tenemos un cameo del Panama Hilton junto a la bahía de Panamá:

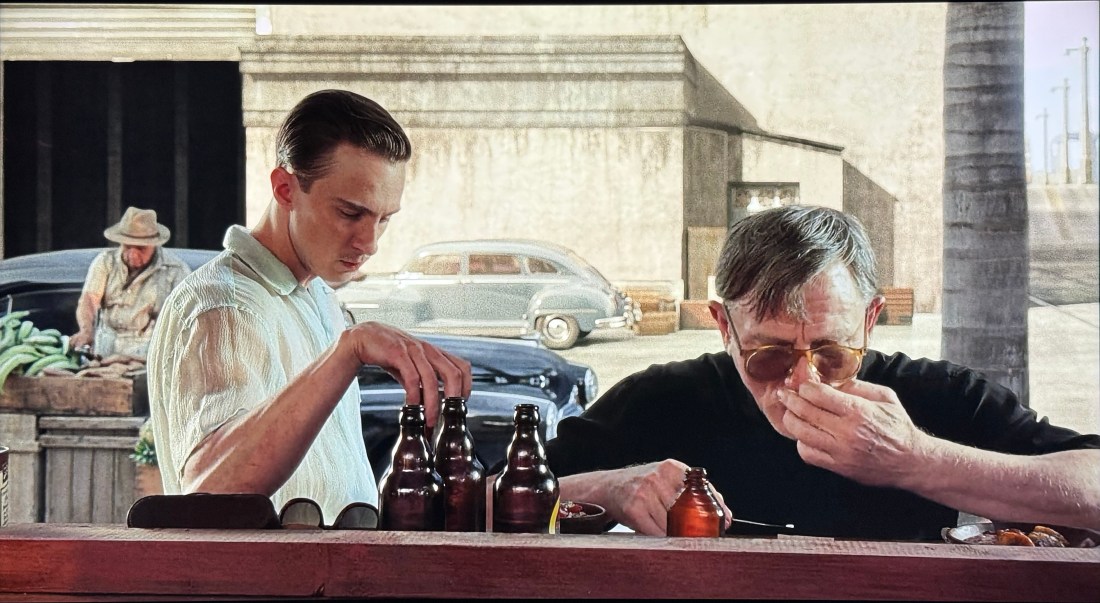

Y una farmacia y droguería llamada Zona Canal con un montón de sombreros al frente (por si no la habían captado). Lee prende un bate y Allerton le consigue una botellita de paregórico.

Finalmente, Lee se mete un hit de perico con los faroles y las rampas de las esclusas al fondo. No intenten nada de esto en casa, amiguitos.

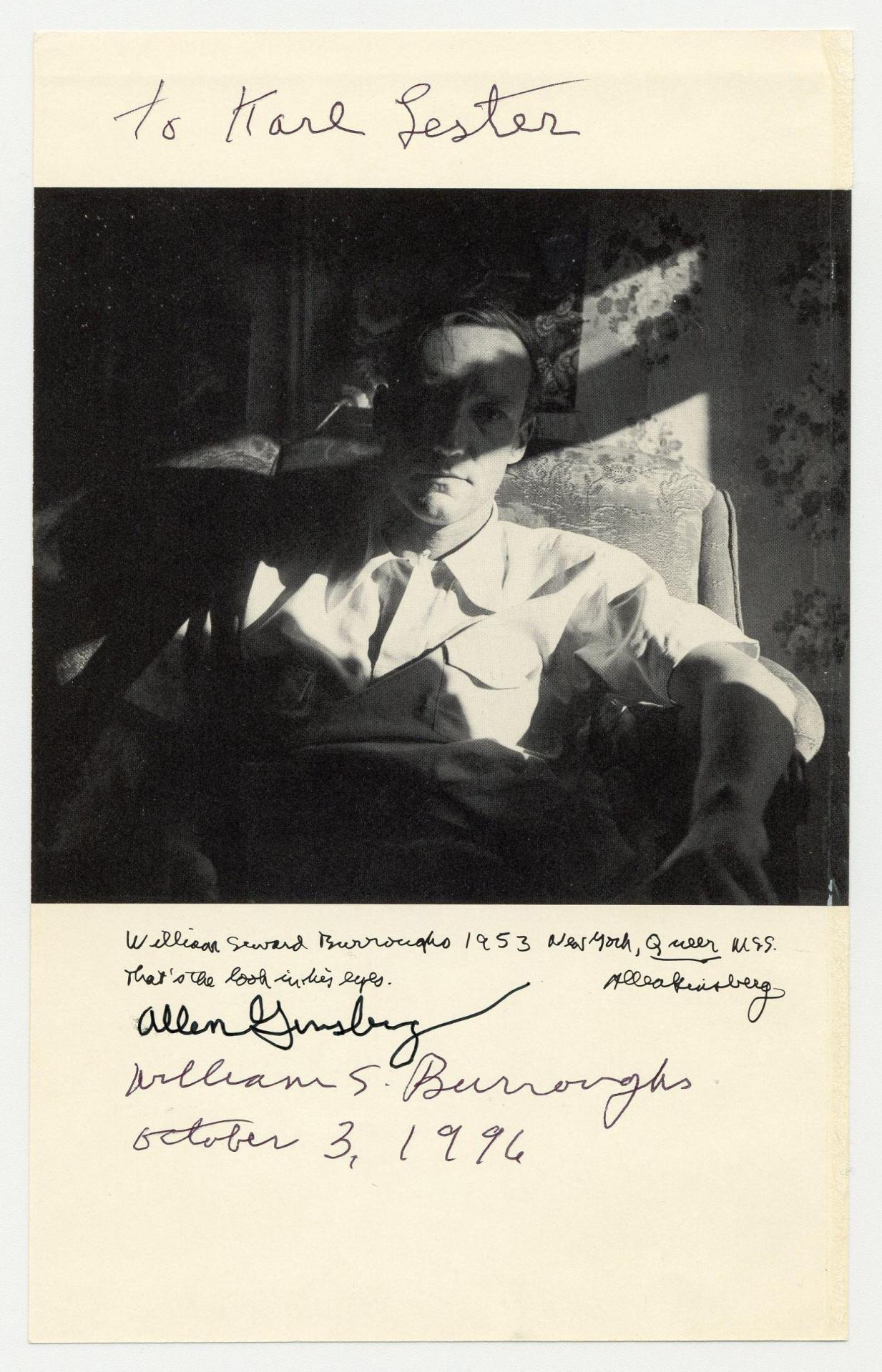

Capítulo 2: Burroughs Burroughs Burroughs

No es un secreto que entre mis crónicas favoritas del Panamá de ayer están las que escribió William Burroughs. Ya en el pasado hemos hablado por acá sobre cómo describía nuestros bajos mundos en su primera Carta del yagé y sobre el misterio de la taberna Blue Goose, que al final resultó ser La Gruta Azul. Bueno, para añadir a este corpus, les presentamos hoy las secciones panameñas de su novela Queer, escrita en 1953 pero publicada en 1985. La edición expandida publicada en 2010 recrea un capítulo perdido dedicado a Panamá. Y dice:

Lee was reading aloud to Allerton a lurid account of the jungle dives in Panama: “‘Anything goes in these dens at the end of perilous muddy roads in the jungles that surround Panama City. . . . Snakes, mosquitoes carrying yellow fever and malaria are the least of the hazards one can expect to encounter. Dope peddlers lurk in the lavatory, offering their wares and sometimes darting out of a toilet booth to administer an injection without waiting for consent. Swamps teeming with alligators can swallow an unwary visitor without a trace. . . .’”

“Well,” said Allerton, “what are we waiting for?”After making an arrangement with a cabdriver to take them there and back for twenty dollars, Lee and Allerton entered a tin-roofed shack with a bar along one wall, some tables, and several listless middle-aged B-girls with barely the energy left to hustle and mooch. The only thing lurking in the lavatory was an insolent, demanding attendant. . . . They did buy some very good green from the cabdriver, whose name was Jones.

The hotel was air-conditioned. The eggs at breakfast were greasy and repulsive. Allerton discovered that you could buy paregoric in the drugstores without prescription.

“There was a number on the jukebox in one of the interchangeable bars, called “Opio y Anejo”—“Opium and Rum.” Chinese, Lee gathered, since it was sung in a yacking falsetto“Want to pick up on some grass?”

“That will do for a start.”

They got in a cab and smoked the tea. It was very good weed. Lee had never smoked better. Lee asked about getting some H and C.

“Sure man, anything. But it costs, see? Twenty dollars a gram.”

Lee cashed a fifty-dollar traveler’s check in a curio store, buying a wallet and a Panama hat. His senses were numbed with paregoric and rum and weed. They went around to a series of bars and hotels and whorehouses, looking to score for H and C—for Henry and Charlie.

Allerton passed out on the backseat. Weed always made him sleep. Lee sniffed some stuff in the car. He couldn’t tell whether it was anywhere or not. The fifty dollars was gone.

Next day Lee said: “In 1873 the pope issued a bull to the effect there would be no more discussion of the Immaculate Conception. I am issuing a similar bull in regard to that fifty dollars.

El otro texto panameño es la sección inicial del apéndice, «Two years later: Mexico City return». Y dice:

Every time I hit Panama, the place is exactly one month, two months, six months more nowhere, like the progress of a degenerative illness. A shift from arithmetic to geometric progression seems to have occurred. Something ugly and ignoble and subhuman is cooking in this mongrel town of pimps and whores and recessive genes, this degraded leech on the Canal.

A smog of bum kicks hangs over Panama in the wet heat. Everyone here is telepathic on the paranoid level. I walked around with my camera and saw a wood and corrugated iron shack on a limestone cliff in Old Panama, like a penthouse. I wanted a picture of this excrescence, with the albatrosses and vultures wheeling over it against the hot gray sky. My hands holding the camera were slippery with sweat, and my shirt stuck to my body like a wet condom.

An old hag in the shack saw me taking the picture. They always know when you are taking their picture, especially in Panama. She went into an angry consultation with some other ratty-looking people I could not see clearly. Then she walked to the edge of a perilous balcony and made an ambiguous gesture of hostility. I walked on and shot some boys—young, alive, unconscious—playing baseball. They never glanced in my direction.

Down by the waterfront I saw a dark young Indian on a fishing boat. He knew I wanted to take his picture, and every time I swung the camera into position he would look up with young male sulkiness. I finally caught him leaning against the bow of the boat, idly scratching one shoulder. A long white scar across right shoulder and collarbone. Such languid animal grace. I put away my camera and leaned over the hot concrete wall, looking at him. I was running a finger along the scar, down across his naked copper chest and stomach, every cell aching with deprivation. I pushed away from the wall, muttering “Oh Jesus,” and walked away, looking around for something to photograph. Many so-called primitives are afraid of cameras. They think it can capture their soul and take it away. There is in fact something obscene and sinister about photography, a desire to imprison, to incorporate, a sexual intensity of pursuit.

A Negro with a felt hat was leaning on the porch rail of a wooden house built on a dirty limestone foundation. I was across the street under a movie marquee. Every time I prepared my camera he would lift his hat and look at me, muttering insane imprecations. I finally snapped him from behind a pillar. On a balcony over this character a shirtless young man was washing. Negro and Near Eastern blood, rounded face, café-au-lait mulatto skin, smooth body of undifferentiated flesh with not a muscle showing. He looked up from his washing like an animal scenting danger. I caught him when the five o’clock whistle blew. Old photographer trick: wait for distraction.

I went into Chico’s Bar for a rum Coke. I never liked this place, nor any other bar in Panama, but it used to be endurable and had some good numbers on the jukebox. Now nothing but this awful Oklahoma honky-tonk music, like the bellowing of an anxious cow: “Drivin’ Nails in My Coffin,” “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels,” “Your Cheatin’ Heart.”

The servicemen in the joint all had that light-concussion Canal Zone look: cow-like and blunted, as if they had undergone special G.I. processing and were immunized against contact on the intuition level, telepathic sender and receiver excised. You ask them a question, they answer without friendliness or hostility. No warmth, no contact. Conversation is impossible. They just have nothing to say. They sit around buying drinks for the B-girls and make lifeless passes, which the girls brush off like flies, and play that whining music on the jukebox. One young man with a pimply adenoidal face kept trying to touch a girl’s breast. She would brush his hand away, then it would creep back as if endowed with autonomous insect life.

A B-girl sat next to me, and I bought her one drink. She ordered good Scotch, yet. “Panama, how I hate your cheatin’ guts,” I thought. She had a shallow bird brain and perfect stateside English, like a recording. Stupid people can learn a language quick and easy because there is nothing going on in there to keep it out.

She wanted another drink. I said, “No.”

She said, “Why are you so mean?”

I said, “Look, if I run out of money, who is going to buy my drinks? Will you?”

She looked surprised, and said slowly, “Yes. You are right. Excuse me.”

I walked down the main drag. A pimp seized my arm. “I gotta fourteen-year-old girl, Jack. Puerto Rican. How’s about it?”

“She’s middle-aged already,” I told him. “I want a six-year-old virgin and none of that sealed-while-you-wait shit. Don’t try palming your fourteen-year-old bats off on me.” I left him there with his mouth open.

I went into a store to price Panama hats. The young man behind the counter started singing: “Making friends, making money.”

“This spic bastard is strictly on the chisel,” I decided.

He showed me some two-dollar hats. “Fifteen dollar,” he said.

“Your prices are way out of line,” I told him, and turned and walked out.

He followed me onto the street. “Just a minute, Mister.” I walked on.

Siguiente misión: rebuscar entre los archivos de Burroughs para encontrar esas fotos tomadas en Panamá. Me huele a una propuesta de beca de investigación.